05.17

A while ago I read this excellent article by Evil Mad Scientist Laboratories describing the need for some form of visual diff tool for open hardware projects. I had been thinking this was a great idea, but while working on a recent project, decided to actually start implementing something. I use the gEDA suite of tools, so that is what I’m creating this for, but the majority of the plumbing should be reusable for other file formats.

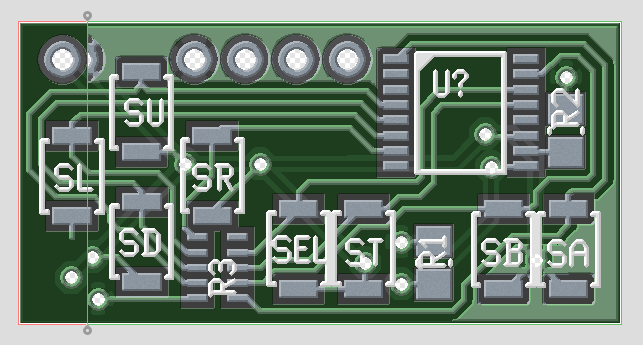

The first piece of this puzzle for me was automatically making image files of my schematics and PCBs that have changed and adding them to each commit. GitHub has image diffing capabilities built in, so this works great. I implemented this a pre-commit hook in .git/hooks/. My git hooks can be found here. I have designed them to work with the git-hooks tool by Benjamin Meyer.

This script seems to work fine for me, though I’m open to suggestions for improvements. My major issues with how the hooks work (which are more issues with git than my hook) are

- The status message in the auto-generated commit comments is not being updated with the new image files and

- Hooks don’t get pushed into remotes

The first issue feels like a bug to me, but I suspect that it was done intentionally for some reason I’m not aware of. I have played with a work around by adding a prepare-commit-msg hook that just regenerates the commit message comments, but I have tested the pre-commit hook enough that I don’t feel I need to be aware of the addition of the images.

The second issue I am told is a security issue as it would cause arbitrary code to be executed on the machines of others who might clone (and possibly even the server). One nice feature of the git-hooks tool is that it can use hooks in a local repo directory, so if you include my scripts in the git_hooks repository, you just need to run ‘git hooks –install’ and you will have the hooks working. Without that tool, you can just manually copy them into the proper file in the .git/hooks/ directory.

This method works well if I want to view visual diffs online, but sometimes I might be offline or perhaps I just don’t want to push my project to a public GitHub repo. For that, I plan to make some simple scripts that call visual diffing tools on my local repository. Git has the capability to set your git diff tool, so my plan is to write a wrapper script that picks the right tool based on file types. This script might also generate an image from files that cannot be diffed directly and don’t have the above auto generated files

Edit: Of course not 20 minutes after I publish this post I discover schdiff, a tool bundled with gEDA since the start of 2012 that is designed to hook into git-difftool to provide a visual diff of gschem .sch files. One format down, some more to go.

Edit 2: Less than a day later and I discover there is also a pcbdiff tool on my computer that came with gEDA pcb. In Arch Linux, it installs to /usr/share/pcb/tools/pcbdiff, but it is not in the path, so in my .bashrc I just added ‘export PATH=”$PATH:/usr/share/pcb/tools”‘ at the end. I feel pcbdiff outputs images that are too low a resolution, plus it can’t handle when the .pcb files change in physical size, so I might submit a patch or two. Long story short, now I just need to make a script that auto-calls these diff tools based on the file type.